Purpose

The purpose of this brief is to support pediatric and family medicine care teams in adapting their practices to better meet the needs of adolescents (ages 12-17) and their families by implementing behavioral-developmental health screening and response.

Definition

Behavioral-developmental health screening and response is an approach to pediatric primary care in which care teams administer screenings to identify behavioral health conditions (e.g., depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders), adversity (e.g., trauma and abuse), and health-related social needs (e.g., homelessness and food insecurity) and provide targeted interventions, referrals (if needed), and close follow-ups.

Adolescence is a period of profound transformation, marked by unique challenges that can significantly impact well-being. Adolescents experience hormonal shifts during puberty that trigger synaptic pruning, myelination, and neurotransmitter changes in the brain and can contribute to dangerous or risky behavior.1–6 They also navigate increased independence and autonomy, explore their identity, and develop their views and attitudes toward peers, friends, partner relationships, and issues of safety and violence.7,8 Compounding these changes, almost all (95%) adolescents (ages 13–17) use a social media platform, which can increase the risk of depression, anxiety, body image issues, and bullying—especially for girls.9–12

The effects of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), such as abuse, neglect, violence, and parental substance abuse, may become more pronounced during adolescence and manifest as developmental delays, learning disabilities, behavioral health conditions, behavioral problems, and physical health issues.13–18 Having unmet health-related social needs, such as lack of access to healthy food or housing insecurity during childhood, can also contribute to psychosocial problems like depression, anxiety, substance use, and bullying during adolescence.19–21

Many adolescents struggle with behavioral health issues, and the rates are increasing.22–24 In 2022, 20% of adolescents reported at least one major depressive episode in the past year (up from 8.1% in 2009), 21% reported symptoms of anxiety, and 560 per 100,000 reported an eating disorder (up from 112 per 100,000 in 2017).24–26 Suicide is the second leading cause of death among adolescents ages 12-17, and drug overdose deaths (driven by fentanyl) are a growing issue.24,27

Given the significant developmental, social, and behavioral health challenges adolescents face, it is important for pediatric primary care teams to move beyond a focus on physical health and infectious disease by implementing behavioral-developmental health screening and response. While there isn't yet a large body of research evaluating a fully standardized and comprehensive behavioral-developmental health screening and response approach for age groups (i.e., ages 12 to 17), individual types of screening and interventions addressing social, emotional, and behavioral health have demonstrated feasibility and effectiveness for improving adolescent behavioral health outcomes and increasing resilience.28–33 By administering screenings, pediatric and family medicine providers can effectively identify adolescents with unmet behavioral health, developmental, and health-related social needs, enabling the provision of timely and targeted interventions, appropriate referrals, and close follow-up to improve outcomes.29–31

At its core, behavioral-developmental health screening and response involves screening to identify social, emotional, and behavioral health needs and providing appropriate evidence-based targeted interventions, referrals (if needed), and close follow-up. Although there is evidence that systematically addressing social, emotional, and behavioral health needs in adolescents leads to better outcomes, this approach to care is still developing, and there is considerable heterogeneity across different programs.34 However, there are numerous programs that implement behavioral-developmental health screening and response models with children ages 0-5 (PDF - 327 KB), providing data on how effective interventions can be structured.35–37 Table 1 (below) takes the common components identified in programs for ages 0-5 and applies them to adolescents ages 12-17, providing a list of relevant activities for each component. This list serves as a reference for understanding potential activities when implementing behavioral-developmental health screening and response models but is not meant to be prescriptive or exhaustive.

There are several key differences to note in behavioral-developmental health screening and response for adolescents compared to children. For adolescents, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that clinicians:

- Maintain relationships with families and patients to help patients develop autonomy in healthcare decision-making.38

- Provide developmentally appropriate care that protects adolescent confidentiality in the health care billing and insurance claims process in compliance with state and federal laws.39,40

- Communicate and collaborate with schools, when possible, to determine whether patients are utilizing school-based behavioral and developmental health services and facilitate coordination of care, if so.41

Table 1. Behavioral-Developmental Health Screening and Response Common Components Adapted for Adolescents Ages 12-17

# | Common Components | Relevant Activities |

1 | Trauma-informed approach |

|

2 | Two-generation approach |

|

3 | Provider/staff training |

|

4 | Anticipatory guidance |

|

5 | Parent/ caregiver education |

|

6 | Team-based care |

|

7 | Standard workflows for screening and response |

|

8 | Connection to community resources |

|

9 | Data utilization |

|

How a practice or health system chooses to implement behavioral-developmental health screening and response is flexible and customizable based on available resources in the practice and community, staff expertise, and specific organizational goals. The programs listed below illustrate how the components and relevant activities can be implemented and demonstrate the feasibility of this approach.

- Barbara Bush Children’s Hospital and Tufts University School of Medicine ACEs and Resiliency Program: This model involves team-based primary care, which screens and responds to trauma, family stressors, adolescent behavioral health symptomology, and health-related social needs. An integrated behavioral health therapist delivers evidence-based prevention and treatment services and provides referrals to community supports to address health-related social needs and build resiliency for families and individual patients (ages 0 to 21). Within one year, the Barbara Bush Children’s Hospital and Tufts University School of Medicine ACEs and Resiliency Program achieved an 88.46% trauma screening completion rate across 14 pediatric primary care practices, increased the rate of identified post-traumatic symptomology from 16.3% to 57.1%, and connected 46.5% of previously unconnected patients with post-traumatic stress disorder symptomology to behavioral health resources.42

- The Bayview Child Health Center-Center for Youth Wellness Integrated Pediatric Care Model: This model involves team-based care where medical assistants screen children and adolescents (ages 0 to 19) for exposure to ACEs and toxic stress upon check-in for routine visits in the pediatric setting. Pediatricians share relevant information about stress and its effects on health and development, ask about symptoms associated with toxic stress, and provide anticipatory guidance or referral to integrated care based on the screening results and behavioral-developmental health symptomology. Upon referral, care coordinators provide home visits and targeted education to families to enhance understanding and coping strategies and provide trauma-informed, evidence-based therapies in collaboration with community partners.

- The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) Center for Violence Prevention Growing Resilience in Teens (GRIT) Program: This team-based program proactively addresses trauma for youth and adolescents (ages 8 to 17) who are patients at two CHOP Primary Care Center locations. The pediatric primary care providers screen children and families to identify trauma exposure, post-traumatic stress symptoms, depression, anxiety, suicidality, and health-related social needs and provide direct referrals to peer-support groups; home, school, or community-based case management support; or a comprehensive trauma-informed behavioral health assessment. From July 2021 to August 2022, the CHOP GRIT Program team completed 125 assessments, connecting 32 youths with trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy and 93 youths with case management support and assistance.43 The GRIT team communicates closely with the providers and social workers to ensure an integrated, coordinated plan for each family. The GRIT program also receives referrals from after-school programs in West and Southwest Philadelphia and provides peer-support groups in some of these schools.

1. Set Goals and Get Ready.

Initiating behavioral-developmental health screening and response for adolescents ages 12-17 requires careful planning and preparation. It’s important to establish clear objectives and proactively address the unique challenges of working with this age group. Consider the following:

- How will you reduce barriers to care for adolescents? Adolescents are less likely than younger children to complete a well-child visit.44–48 They most often cite financial strains (e.g., high care costs, lack of insurance, and prior authorization issues), system and structural issues (e.g., medication shortages, limited clinic space, disparate health technology, long wait times, and lack of coordinated care), communication challenges, and care navigation issues as barriers to care.49 Your practice can implement team-based care and partner with community-based organizations that provide insurance navigation, financial assistance, and interpretation services. Your practice can also try opening before or closing after traditional work hours and partnering with school-based providers and health centers to increase the availability and space for appointments.

What are the state and federal laws around adolescent autonomy, privacy, and confidentiality? Adolescents have greater autonomy and legal rights regarding privacy and confidentiality. Your practice can conduct a thorough review of state and federal laws (PDF - 2.8 MB) (e.g., the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (or HIPAA) and state-specific minor consent laws) or consult with legal counsel to determine which services adolescents can consent to on their own and which ones require parental consent.

How will you, in compliance with state and federal laws, respect adolescent autonomy in decision-making regarding their care and the sharing of their health information? Your practice can use a shared decision-making approach to empower adolescents to actively participate in their care. You can ensure that they have opportunities for private conversations with providers, away from parents or guardians, during which you can clearly explain consent procedures and emphasize their right to make informed decisions.

What communication protocols will you establish among care teams, staff, and families to ensure appropriate information sharing while maintaining confidentiality? Your practice can provide written policies and educational resources for providers and staff outlining adolescent rights to autonomy, privacy, and confidentiality, including a list of services adolescents can consent to independently. You can also provide regular training to all staff on these laws and policies, as well as how to document autonomy and consent in the adolescent's medical record.

How will you identify and respond to families with adolescents overdue for a well-child visit or who did not attend a scheduled behavioral health appointment? Your practice can use patient registries to identify and track outreach to families with adolescents overdue for a well-child or acute visit. You can use auto-dialers, phone calls, text messages, emails, direct mailers, and direct messages in patient portals to remind families of upcoming or overdue visits or even convert acute visits to well-child visits or vice versa.

TIP: Create initial aim statements.

Create initial aim statements to describe what you would like to achieve from your efforts. Aim statements can provide common language and shared understanding for garnering buy-in and support; guidance for selecting screening tools, workflows, and referral pathways; justification for staff, budget, and other resource allocation; and measurable targets for tracking progress and evaluating effectiveness. To get started, consider this aim statement worksheet (PDF - 215 KB) or the formula and examples below.

By [DEADLINE], we will [OUTCOME/ACTION] for [INTENDED POPULATION] by [GOAL] (as measured by [DATA SOURCE]).

- Example #1: Increase the proportion of adolescents aged 12-17 who receive screening for depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) for Adolescents (PHQ-A) during their annual well-child visits by [percentage] within [timeframe].

- Example #2: Increase the number of adolescents aged 12-17 with a Pediatric Symptom Checklist-17 (PSC-17) score >15 who receive timely referrals to appropriate behavioral health services when needed by [percentage] within [timeframe].

- Example #3: Increase the percentage of adolescents aged 12-17 with a PRAPARE® score > 0 who receive an appropriate community referral by [percentage] within [timeframe].

Once you have considered key challenges and set initial aims, develop a realistic timeline for implementation. Pick a start date and work backward from there, building in time to garner support from leadership and clinical and administrative staff and prepare adolescents and families in your practice or system.

2. Redesign the Pediatric Care Team and Foster School-Based Partnerships.

AAP recommends that pediatric practices use a strengths-based approach in the care of adolescents that promotes safe, stable, and nurturing relationships and builds resiliency.50 Safe, stable, and nurturing relationships with parents, caregivers, family, peers, and teachers, along with other positive childhood experiences, act as protective factors for adolescents. Safe, stable, and nurturing relationships promote healthy development and positive health outcomes for adolescents throughout their lives by buffering adversity and building resiliency.51–56 Adolescents with higher levels of resiliency report having fewer mental health problems.57

AAP also recommends that pediatric practices address adolescent behavioral health and developmental concerns by implementing a patient-centered, adolescent medical home model with coordinated or integrated behavioral health care.38 In addition, AAP recommends, when possible, that pediatric providers communicate and coordinate with schools and school-based health centers to provide adolescents with access to a medical home.41 About 96% of public schools offer some form of mental health services—they may have a licensed clinical social worker or psychologist located in the school or school-based health center—however, understaffing can limit the reach of these services.58,59

Behavioral Health Interventions in Pediatric Primary Care Settings

Pediatric primary care practices can use integrated behavioral health, like Barbara Bush Children’s Hospital and Tufts University School of Medicine ACEs and Resiliency Program, as a foundation to implement behavioral-developmental health screening and response. To integrate behavioral health, pediatric primary care practices can 1) provide behavioral health training to the care team, 2) coordinate behavioral health care using web-based or telephone consultation, 3) co-locate behavioral health clinicians within primary care, or 4) implement integrated or other team-based care approaches like collaborative care or patient-centered medical homes.60–63

Table 2 in the Evidence of Effectiveness section summarizes statistically significant outcomes data for children and adolescents receiving integrated behavioral health care in pediatric primary care practices. As outlined in the table, integrated behavioral health models, especially those that include team-based care and target adolescents with positive screenings, have demonstrated effectiveness in improving behavioral health outcomes for adolescents in pediatric primary care settings.

If you have the resources and opportunity, consider expanding the care team to help distribute new roles and responsibilities. The most common roles added to pediatric care teams working with adolescents include:

- Care managers or coordinators: Provide anticipatory guidance, parenting coaching, and adolescent development support; conduct intake and screening processes; facilitate referrals and communication with school-based health centers and school-based resiliency-building programs; connect families with community resources; and/or provide care coordination and follow-up.64

- Behavioral health clinicians (e.g., psychologists, professional counselors, marriage and family therapists, and clinical social workers): Provide evidence-based treatments that reduce the negative effects of trauma and increase resilience for adolescents via telehealth or onsite in pediatric primary care practices, school-based health centers, or school-based settings, including:65

Partnerships with School-Based Settings

Outside of primary care settings, schools are the most common healthcare service setting for children and adolescents.66 Several studies have assessed the implementation of evidence-based approaches for increasing resilience and addressing behavioral health symptomology for adolescents in school-based settings. These interventions typically involve psychoeducational techniques, cognitive-behavioral therapy, problem-solving therapy, mindfulness and target cognitive competence, problem-solving/decision-making, cooperation and communication skills, and coping mechanisms.67 Table 3 in the Evidence of Effectiveness section summarizes statistically significant outcomes data for adolescents participating in resiliency-based interventions or receiving integrated behavioral health care in school-based settings. As outlined in the table, these resiliency-based interventions in school-based settings, particularly those involving cognitive behavioral therapy and multicomponent approaches, have demonstrated effectiveness in increasing adolescent resiliency. They have also demonstrated effectiveness in improving adolescent behavioral health outcomes, specifically illicit substance use and internalizing problems.

School-based health centers and school-based resiliency programs can be vital extensions of the pediatric care team. Similar to the team-based model of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia GRIT Program, you can establish formal agreements and clear communication channels with these school-based health centers and resiliency programs, coordinate screening efforts with them, and develop care pathways where adolescents identified in the primary care setting can be seamlessly referred to and receive services in them (and vice versa). You can use this online school-based health center map to find your community’s participating school districts and school-based health centers.

TIP: Implement warm handoffs/same day visits.

Warm handoffs within the Primary Care Behavioral Health model of care between pediatric care team members have been associated with increased first appointment show rates, improved patient engagement, fewer no-shows, fewer cancelations, shorter time between referral and initial scheduled behavioral health visit, and more total behavioral health visits.68–70

TIP: Huddle as a team to prepare for the day.

Example discussion topics for your huddle can include increasing the use of the PHQ screening tool for behavioral health follow-up visits, identifying patients who may need an additional reminder call or transportation support, and identifying patients who may benefit from a warm handoff or collaborative visits with a behavioral health clinician.

TIP: Up-train your team.

If you are unable to expand your care team to address gaps in knowledge, skills, and experience, up-train them instead. Clinical and administrative staff can be trained to support health-related social needs through referrals and connection tracking. Primary care providers can receive additional training (see examples listed below) to conduct resiliency-building and behavioral health interventions for adolescents.

Sample Targeted Intervention Trainings for Providers

- Adolescent Substance Use ECHO Training - American Academy of Pediatrics

- Mental Health Training for Pediatric Primary Care Providers - REACH Institute

- Nurturing Resilience in Children and Adolescents Training - Pediatric Nursing Certification Board

- Pediatric Mental Health ECHO Training - American Academy of Pediatrics

3. Conduct Training and Education.

Conduct foundational training and education to increase staff and provider understanding of trauma-informed care and how the unique experiences of adolescence can significantly impact brain development, risk-taking, and subsequent long-term health.

Sample Foundational Trainings for Providers

- Addressing Childhood Trauma Through Trauma-Informed Care - American Medical Association

- Integrating Adolescent Brain Development into Child Welfare Practice with Older Youth - National Association of Social Workers

- Trauma-Informed Care: Self-Directed Learning - American Academy of Pediatrics

TIP: Provide trauma-informed scripts to your team.

Trauma-informed language builds a sense of safety and trust through transparency, choice, and collaboration. The sample script excerpts below use the word “all” to prevent families from feeling singled out. The statements explain why the provider and patient are rooming alone and using questionnaires and have a choice embedded in them.

Sample Trauma-Informed Script Excerpts for Clinical Rooming Staff

- For parents: “We start all visits with adolescents alone if they’re comfortable with that and then bring in the parents afterward. It gives us a chance to get to know the adolescent as an individual a bit better. I will come and get you as soon as we are done and before the provider comes in. Is that okay with you?”

- For adolescents: “We ask all patients your age to complete written questionnaires. It helps us to better understand how you are doing so that we can offer the best care. I can give it to you to complete on your own. Your provider will then review your answers with you. Does that work for you?”

You can create scripts for your practice using the examples in the following guides:

- ACE-Q User Guide for Health Professionals (PDF - 2.8 MB) - Bayview Child Health Center

- ACE Screening Sample Scripts for Pediatric Clinical Teams (PDF - 551 KB) - ACEs Aware

4. Adopt Validated Screening Tools and Standardized Workflows.

Select the screening tools and workflows your care team, including any school-based partners, will use to identify adolescents and families who have experienced trauma and behavioral health symptomology and have unmet health-related social needs, such as transportation, housing, or food insecurity.

You can use this screening tool finder or the sample list below to identify validated screening tools for behavioral, social, and emotional health, child development, and health-related social needs for adolescents ages 12-17.71 When implementing a new screening tool, examine its validation process and align your workflow as closely as possible to the validated methodology for each tool you choose to use. For example, the PHQ-A, PSC-17, and the Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends, Trouble (CRAFFT) screening tool are all validated as self-completed written screeners for adolescents.

The tools listed below are available in multiple languages to support an equitable model for all patients. Please note that, for this age group, the PHQ-A and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) are superior to the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2), especially regarding suicidality, and are useful for supporting diagnosis and tracking intervention response.72–76 As such, the PHQ-2 is not listed.

Validated Screening Tools for Adolescents Ages 12-17

Depression

- PHQ-9 (PDF - 39.9 KB) (Ages 11 years+)

- PHQ-9 Modified for Adolescents (PHQ-A) (PDF - 24.7 KB) (Ages 11-17 years)

Anxiety

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) (PDF - 130 KB) (Ages 11 years+)

- Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED) (PDF - 165 KB) (Ages 8-18 years)

Substance Use

- CRAFFT (Ages 12-21)

Suicidality

- Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) (PDF - 181 KB) (Ages 6 years+)

Behavioral, Social, and Emotional Health Screening Tools

- HEADSS (for topics covering home, education (i.e., school), activities/employment, drugs, suicidality, and sex; up to age 25)

- Pediatric Symptom Checklist—Youth Report (Y-PSC) (PDF - 40.9 KB) (Ages 11 years+)

- Pediatric Symptom Checklist (PSC) (PDF - 40.9 KB) (Ages 4-17 years)

- The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (Ages 2-17 years)

Health-Related Social Needs

- Accountable Health Communities Health-Related Social Needs Screening Tool (PDF - 328 KB) (All ages)

- Screen and Intervene: A Toolkit for Pediatricians to Address Food Insecurity (All pediatric ages)

- The Hunger Vital Sign: A New Standard of Care for Preventive Health (All pediatric ages)

- The PRAPARE® Screening Tool (Ages 18 years+, has been adapted for pediatric use (PDF - 519 KB))

Trauma

- Pediatric ACEs and Related Life Events Screener (PEARLS) (PDF - 187 KB) (Ages 0-19 years)

- Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen (CATS) (Ages 3-17 years)

- Child Trauma Screen (CTS) (Ages 6-18 years)

Also, consider confidentiality when planning the screening workflow. You can, for example, implement a workflow where adolescents complete written screening tools alone in the exam room. Be sure to also implement workflows that support ongoing close follow-up for adolescents with positive behavioral health screenings. You can:

- Emphasize that they have their follow-up appointment scheduled prior to leaving the office.

- Conduct targeted outreach to adolescents who did not attend the scheduled well-child visit or behavioral health appointment.

- Use medication refills and other calls to the practice to review if follow-up is needed.

5. Identify Community Resources.

Identify, if you haven't already the government and community programs available to help you meet the needs of the adolescents and families you serve. Your pediatric primary care practice or health system will not be able to address every need identified during screening. Establishing direct relationships with programs in schools and other community-based settings can further facilitate successful connections for families.

For example, your care team can screen for transportation barriers. If a patient and their family screen positive, they can:

- Provide materials on the available public transportation options.

- Offer assistance with completing applications for transportation assistance programs, vehicle donation programs, reduced transit fare programs, and free or subsidized passes/vouchers for trains, buses, rideshares, and taxis.

- Provide referrals to community resources.

- Purchase passes for buses, taxis, or rideshares using funds from the practice’s budget, grants, or other external sources.

You can use this online school-based health map to find the school districts and school-based health centers in your community. You can also use this online social care database or 211 to find local community resources, including:

- Case management programs

- Behavioral health providers

- Crisis support services

- Childcare agencies

- Basic needs assistance

- Legal assistance

- Peer support

- Health and social services programs

6. Align the Electronic Health Record System to Support Workflows, Data Collection, and Quality Improvement.

Both medical and behavioral health staff need to be able to access information seamlessly and securely to support coordinated and collaborative care. Any existing silos among clinicians and limitations in the electronic health record (EHR) can significantly hinder this crucial information flow. Work with care team members and your information technology staff or vendor to conduct a thorough assessment of current information-sharing practices and identify barriers within the EHR that prevent integrated access to medical and behavioral health records among staff.

Partner with your information technology staff or vendor to develop EHR models capable of aligning workflow and data reports. Additionally, creating structured data fields early on can support the creation of essential EHR reports for tracking the rates of screening, positive risks identified, and interventions provided. Where appropriate and with strict adherence to privacy regulations, explore opportunities for securely sharing relevant data (PDF - 6 MB) (e.g., screening results and progress in interventions) to improve care coordination and outcomes with school-based health centers and other external partners. Plan to conduct regular assessments of your EHR with your technology staff or vendor to identify and troubleshoot points of vulnerability in which adolescent confidentiality and privacy may be compromised if appropriate safeguards are not put in place.

Your care team, practice, or health system can create and use data registries (PDF - 4.1 MB) and data reports to support implementing quality improvement methodologies for behavioral health screening and response—such as the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle—and the data can also be used to create patient registries that provide increased support and connections for patients and families with higher risk, symptomology, barriers, and adversity. Other potential areas to examine during routine quality improvement activities include screening methods, medication prescribing, referral rates, referral connection, treatment adherence, patient satisfaction, and behavioral health remission rates.

TIP: Track metrics across time for all patients.

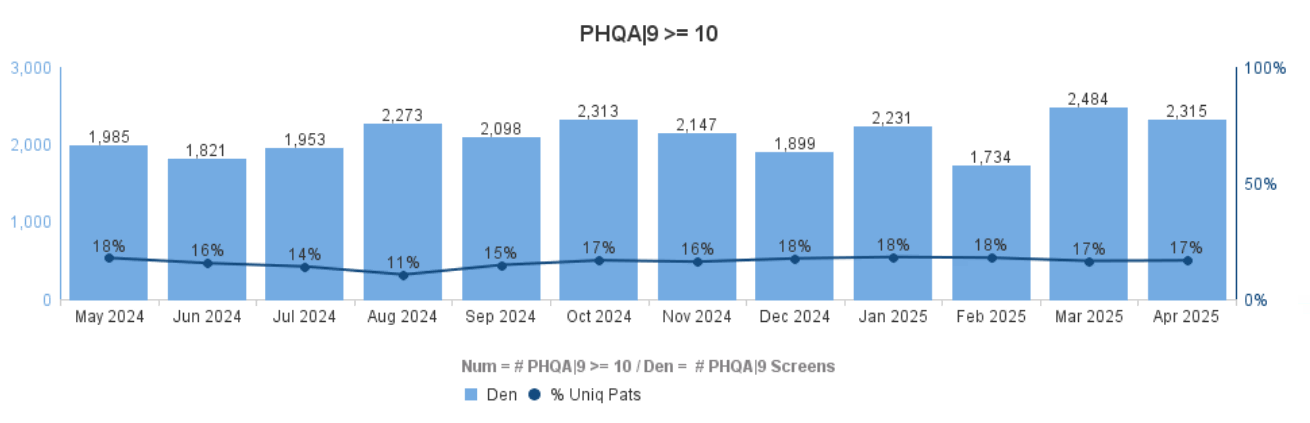

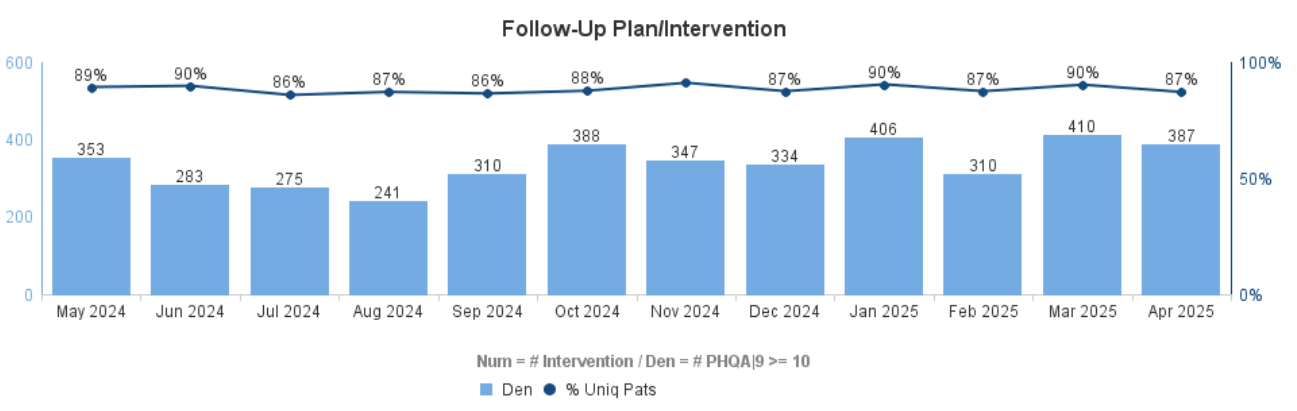

The reporting examples below move beyond examining PHQ-A or PHQ-9 screening rates to also reporting rates of PHQ-A or PHQ-9 scores greater than or equal to (> or >=) 10 over time and rates of follow-up plans and other targeted interventions.

Figure 1. Rates of PHQ-A or PHQ-9 Scores ≥10

Figure 2. Rates of Follow-Up Plans and Other Targeted Interventions

TIP: Closely track patients with identified risks.

The example risk registry below is based on completed PHQ-A screening tools with a score greater than or equal to 10. Providers or trained clinical staff can use such information to consider: Who are the patients with elevated PHQ-A scores? Do they have an upcoming appointment? Have they been connected to community resources? Is the PHQ-A score improving? Was suicidality present? A well-designed report can support rapid chart review and focused patient outreach to increase connection to treatment and resources.

Figure 3. Risk Registry for Patients with PHQ-A or PHQ-9 Scores >10

Next Primary Care Visit | Recall Date | Pos. PHQ Date | PHQ Score | SI | Last PHQ Date | Last PHQ Score | SI | Interventions |

3/25/24 | 5/3/25 | 1/20/25 | 19 | Y | 2/26/25 | 12 | N | Beh Health Ref, Med Rx |

1/29/25 |

| 1/10/25 | 14 | N | 1/10/25 | 14 | N |

|

|

| 12/17/24 | 22 | Y | 2/10/24 | 19 | Y | Beh Health Ref, Med Rx |

3/4/25 |

| 12/10/25 | 12 | Y | 12/10/25 | 12 | Y |

|

| 4/4/25 | 11/19/25 | 12 | N | 1/12/25 | 8 | N | Med Rx |

| 6/12/25 | 11/10/25 | 18 | Y | 1/8/25 | 3 | N | Med RX |

- Adolescents ages 12-17 are facing a significant behavioral health crisis, evidenced by rising rates of depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and suicidality. Implementing behavioral-developmental health screening and response in pediatric primary care and family medicine can address the complex behavioral and developmental needs of adolescents through proactive screening for behavioral health conditions, adversity, and health-related social needs, followed by resiliency-building and behavioral health interventions, and referrals to community supports and close follow-up if needed.

- Comprehensive behavioral-developmental health screening and response has been shown to work for children ages 0-5. While there isn't yet a large body of research evaluating a fully standardized and comprehensive behavioral-developmental health screening and response approach for ages 12 to 17, evidence demonstrates the feasibility of implementing its components for adolescents in pediatric primary care and school settings. Existing programs have achieved high screening rates and have connected youth to necessary behavioral health resources and support.

- There is also moderate research evidence supporting universal screening for depression, anxiety, and intimate partner violence among adolescents. Resiliency-building and behavioral health interventions in pediatric primary care settings have demonstrated effectiveness in improving adolescent behavioral health outcomes better than treatment as usual, particularly when delivered via collaborative care. Resiliency-building and behavioral health interventions in school-based settings have also demonstrated effectiveness in increasing adolescent resilience and improving behavioral health outcomes, including illicit substance use and internalizing problems.

- Pediatric and family medicine practices and health systems can implement behavioral-developmental health screening and response for adolescents by identifying and setting practice goals; redesigning the care team; creating a training and education plan for the care team; adopting standardized tools and workflows; identifying school-based and other community resources; and aligning electronic health records to support workflows, data collection, and quality improvement.

Table 2. Meta-Analyses on Integrated Behavioral Health Models in Pediatric Primary Care Practices

Study | Description | Sample | Outcomes Data for Children and Adolescents |

Hostutler et al. (2024)33 | Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and quasi-experimental studies of integrated behavioral health.

| 27 studies involving 6,879 children and adolescents (ages 0-21) and their caregivers met the study eligibility criteria. | A small overall effect size (SMD = 0.19, 95% CI, 0.11–0.27; p < 0.001) for integrated primary care to usual or enhanced usual care. No statistically significant differences between treatment and prevention trials [Qm(1) = 1.07; p = 30]. Similar effectiveness between co-located and integrated models [Qm(1) = 0.01; p = 0.92]. |

Asarnow et al. (2015)28 | Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) of integrated behavioral health. Note: Most (86%) of the studies included in this meta-analysis had a follow-up period of 6 months. | 31 studies with 35 intervention-control comparisons. 13,129 participants aged 1-21 met the study eligibility criteria.

| A significant advantage for integrated care interventions relative to usual care on behavioral health outcomes for up to 20 months (d = 0.32; 95% CI, 0.21–0.44; p < 0.001). Larger effects for treatment trials that targeted diagnoses and/or elevated symptoms (d = 0.42; 95% CI, 0.29–0.55; p < 0.001) relative to prevention trials (d = 0.07; 95% CI, -0.13–0.28; p = 0.49). It was 66% more likely that a randomly selected youth would experience improved behavioral health outcomes with integrated care compared to usual care and 73% more likely with collaborative care compared to usual care. Both have a substantial advantage over usual care, though collaborative care had a higher likelihood (7 percentage points) of improved outcomes over general integrated care. |

Note: Usual care denotes primary care treatment as usual. Enhanced usual care refers to referral to specialty treatment, brief advice from pediatric primary care providers, and educational materials. Integrated care includes collaborative care, co-location with minimal integration, or behavioral health training, consultation, or telehealth for pediatric primary care providers.

Table 3. Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses on Integrated Behavioral Health Models and Resiliency-Building Interventions in School-Based Settings

Study | Description | Sample | Outcomes Data for Children and Adolescents |

Llistosella et al. (2023)77 | A systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs, cluster trials, quasi-experimental studies, and mixed methods studies. | 27 studies in the systematic review and 16 in the meta-analysis. Participants were adolescents aged 10-19. | Resiliency-based interventions in school-based settings have been shown to increase adolescent resiliency, particularly cognitive behavioral therapy-focused interventions (SMD = 0.20; 95% CI, 0.06–0.34; n = 3) and multicomponent interventions [SMD = 1.45; 95% CI, 0.11–2.80; n = 4), for up to 8 weeks. Only three studies in this meta-analysis looked at duration beyond 8 weeks, and no significant intervention effects were found in those studies. |

Pinto et al. (2021)78 | A systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs. | 17 studies in the systematic review and 13 in the meta-analysis. Participants were children aged <12 and adolescents aged 12–22. | Resiliency-based interventions in school-based settings show initial effectiveness in promoting child and adolescent resiliency (SMD = 0.48; 95% CI, 0.15–0.81; p = 0.02; n = 10) and continued effectiveness for up to 6 months (SMD = 0.12; 95% CI, -0.44–0.69; p = 0.02; n = 3). |

Hodder et al. (2017)79 | A systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs. | 19 studies in the systematic review with a total of 51,867 participants. Participants were children aged 5-9 and adolescents aged 10-18. | Universal resilience-focused interventions in the school setting reduced adolescent illicit substance use, not including tobacco or alcohol use (OR = 0.78, 95% CI, 0.6–0.93; p = 0.007; n = 10). There was a significant intervention effect on adolescent illicit substance use, not including tobacco or alcohol use (OR = 0.84; 95% CI, 0.72 –0.99, p > 0.05; n = 7) at long-term follow-up (12 months). |

Dray et al. (2017)67 | A systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs. | 49 studies in the meta-analysis with 41,521 participants. Participants were children aged 5-9 and adolescents aged 11-18. | Universal resilience-focused interventions in the school setting reduced internalizing problems for adolescents (SMD = -0.19; 95% CI, -0.35 to -0.02; p = 0.03; n = 3). There was also a significant intervention effect on internalizing problems for adolescents (SMD = -0.22; 95% CI, -0.42 to -0.02; p = .03; n = 2) at long-term follow-up (>12 months). |

Knopf et al. (2016)80 | A systematic review of quasi-experimental and observational studies. | 46 studies in the systematic review evaluated onsite clinics serving urban, low-income, and racial or ethnic minority high school students. | The presence and/or use of a school-based health center was associated with:

Note: Only 9 of 46 studies assessed school-based health centers that provided mental health care. |

Adolescent Autonomy, Confidentiality, and Privacy

- Assessing and Supporting Adolescents’ Capacity for Autonomous Decision-Making in Health-Care Settings - World Health Organization

- Confidentiality in the Care of Adolescents: Technical Report - American Academy of Pediatrics

- Minor Consent and Confidentiality: A Compendium of State and Federal Laws (PDF - 2.8 MB) - National Center for Youth Law

Behavioral Health Screening and Response Models for Adolescents

- ACE-Questionnaire User Guide for Health Professionals (PDF - 2.8 MB) - Bayview Child Health Center

- Pediatric Screening Toolkit (PDF - 4.4 MB) - Barbara Bush Children’s Hospital and Tufts University School of Medicine ACEs and Resiliency Program

Resiliency-Building and Behavioral Health Integration in Pediatric Care Settings

- Behavioral Health Integration in Pediatric Primary Care: Considerations and Opportunities for Policymakers, Planners, and Providers (PDF - 326 KB) - Milbank Memorial Fund

- Integrating Behavioral Health Services Within Specialty Practices Serving Pediatric Populations (PDF - 324 KB) - Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

- Patient-Centered Mental Health in Pediatric Primary Care - The REACH Institute

- Pediatric Integrated Care Resource Center - American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

Resiliency-Building and Behavioral Health in School-Based Health Centers

- Adolescent Substance Use Prevention in School-Based Health Centers - School-Based Health Alliance

- The Landscape of School-Based Mental Health Services - Kaiser Family Foundation

- The Building Student Resilience Toolkit - National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments

- Pediatric Mental Health Care Access Programs and School-Based Health Centers (PDF - 1.9 MB) - School-Based Health Alliance

- The Role of School-Based Health Centers in the ACEs Aware Initiative: Current Practices and Recommendations (PDF - 2 MB) - California School-Based Health Alliance

- School-Based Health Center Playbook on Health Care Transition - School-Based Health Alliance

Trauma-Informed Care for Adolescents

- Healthy Outcomes from Positive Experiences (HOPE) Framework - Tufts Medical Center

- Integrating ACEs Screening into Clinical Practice: Insights from California Providers (PDF - 529 KB) - Center for Health Care Strategies

- Screening Adolescents for Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs): Incorporating Resilience and Youth Development (PDF - 979 KB) - ACEs Aware

- Starter Guide: Trauma-Informed Care for Adolescents in Primary Care (PDF - 201 KB) - Michigan Medicine

- Trauma-Informed, Resilience-Oriented Schools Toolkit – National Center for School Safety

Authors

- Monique Thornton, MPH - CEO, Let's Talk Public Health

- Stephen DiGiovanni, MD - Medical Director for the Maine Medical Center Outpatient Clinics and Medical Lead for the MaineHealth Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and Resiliency Program

Other Contributors

- Garrett E. Moran, PhD - Principal, Moran Consulting

- Annaka Paradis, ScM - Lead Research Associate, Westat

- Danielle Durant, PhD, MS, MS, MBA - Principal Research Associate, Westat

- Anne Roubal, PhD - Principal Research Associate, Westat

Acknowledgements

We thank reviewers and other contributors from the Agency of Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ), National Integration Academy Council (NIAC), and staff from Westat and Pantheon for sharing their time and expertise to develop, improve, and publish this work.

Suggested Citation

Thornton M, DiGiovanni S. Behavioral-Developmental Health Screening and Response for Adolescents (Ages 12-17) in Pediatric Primary Care. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; July 2025. https://integrationacademy.ahrq.gov/products/topic-briefs/pediatrics-topic-brief-ages-12-17.

1. Galván A. Adolescent development of the reward system. Front Hum Neurosci. 2010;4. doi:10.3389/neuro.09.006.2010

2. Giedd JN, Blumenthal J, Jeffries NO, et al. Brain development during childhood and adolescence: a longitudinal MRI study. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2(10):861-863. doi:10.1038/13158

3. Blakemore SJ. The social brain in adolescence. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(4):267-277. doi:10.1038/nrn2353

4. Blakemore SJ. Development of the social brain in adolescence. J R Soc Med. 2012;105(3):111-116. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2011.110221

5. Konrad K, Firk C, Uhlhaas PJ. Brain development during adolescence: neuroscientific insights into this developmental period. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 2013;110(25):425.

6. Dumontheil I. Adolescent brain development. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. 2016;10:39-44. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2016.04.012

7. Steinberg L, Morris AS. Adolescent Development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52(Volume 52, 2001):83-110. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83

8. Cyr BA, Berman SL, Smith ML. The Role of Communication Technology in Adolescent Relationships and Identity Development. Child Youth Care Forum. 2015;44(1):79-92. doi:10.1007/s10566-014-9271-0

9. Massarat EAV Risa Gelles Watnick and Navid. Teens, Social Media and Technology 2022. Pew Research Center. August 10, 2022. Accessed March 19, 2025. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2022/08/10/teens-social-media-and-technology-2022/

10. Office of the Surgeon General (OSG). Social Media and Youth Mental Health: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2023. Accessed March 20, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK594761/

11. Haile G, Arockiaraj B, Zablotsky B, Ng AE. Bullying Victimization Among Teenagers: United States, July 2021 – December 2023. Accessed March 20, 2025. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/168510

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data Summary & Trends Report: 2013–2023. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2025. Accessed March 19, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/yrbs/dstr/index.html

13. Maggi S, Irwin LJ, Siddiqi A, Hertzman C. The social determinants of early child development: An overview. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2010;46(11):627-635. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01817.x

14. National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. Excessive Stress Disrupts the Architecture of the Developing Brain. Harvard University Center on the Developing Child; 2009. Accessed March 19, 2025. https://edn.ne.gov/cms/sites/default/files/u1/pdf/se05SE2%20Stress%20Disrupts%20Architecture%20Dev%20Brain%203.pdf (PDF - 253 KB)

15. Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, et al. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256(3):174-186. doi:10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4

16. Herzog JI, Schmahl C. Adverse Childhood Experiences and the Consequences on Neurobiological, Psychosocial, and Somatic Conditions Across the Lifespan. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00420

17. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;14(4):245-258. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

18. Anda RF, Brown DW, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Dube SR, Giles WH. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Prescribed Psychotropic Medications in Adults. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(5):389-394. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.005

19. Paquin V, Muckle G, Bolanis D, et al. Longitudinal Trajectories of Food Insecurity in Childhood and Their Associations With Mental Health and Functioning in Adolescence. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(12):e2140085. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.40085

20. Keen R, Chen JT, Slopen N, Sandel M, Copeland WE, Tiemeier H. Prospective Associations of Childhood Housing Insecurity With Anxiety and Depression Symptoms During Childhood and Adulthood. JAMA Pediatr. 2023;177(8):818-826. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.1733

21. Hatem C, Lee CY, Zhao X, Reesor-Oyer L, Lopez T, Hernandez DC. Food insecurity and housing instability during early childhood as predictors of adolescent mental health. J Fam Psychol. 2020;34(6):721-730. doi:10.1037/fam0000651

22. Office of the Surgeon General (OSG). Protecting Youth Mental Health: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2021. Accessed March 20, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK575984/

23. American Academy of Pediatrics. AAP-AACAP-CHA Declaration of a National Emergency in Child and Adolescent Mental Health. Accessed March 19, 2025. https://www.aap.org/en/advocacy/child-and-adolescent-healthy-mental-development/aap-aacap-cha-declaration-of-a-national-emergency-in-child-and-adolescent-mental-health/

24. Panchal N. Recent Trends in Mental Health and Substance Use Concerns Among Adolescents. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2024. Accessed March 19, 2025. https://www.kff.org/mental-health/issue-brief/recent-trends-in-mental-health-and-substance-use-concerns-among-adolescents/

25. Wilson S, Dumornay NM. Rising Rates of Adolescent Depression in the United States: Challenges and Opportunities in the 2020s. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2022;70(3):354-355. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.12.003

26. Lin BY, Moog D, Xie H, et al. Increasing prevalence of eating disorders in female adolescents compared with children and young adults: an analysis of real-time administrative data. Gen Psych. 2024;37(4). doi:10.1136/gpsych-2024-101584

27. National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death, 2018-2023, Single Race Request. Accessed March 19, 2025. https://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10-expanded.html

28. Asarnow JR, Rozenman M, Wiblin J, Zeltzer L. Integrated Medical-Behavioral Care Compared With Usual Primary Care for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics. 2015;169(10):929-937. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1141

29. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Depression and Suicide Risk in Children and Adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2022;328(15):1534-1542. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.16946

30. US Preventive Services Task Force, Mangione CM, Barry MJ, et al. Screening for Anxiety in Children and Adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2022;328(14):1438-1444. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.16936

31. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Intimate Partner Violence, Elder Abuse, and Abuse of Vulnerable Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Final Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;320(16):1678-1687. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.14741

32. Eder M, Henninger M, Durbin S, et al. Screening and Interventions for Social Risk Factors: Technical Brief to Support the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2021;326(14):1416-1428. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.12825

33. Hostutler CA, Shahidullah JD, Mautone JA, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of pediatric integrated primary care for the prevention and treatment of physical and behavioral health conditions. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. Published online June 12, 2024:jsae038. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsae038

34. Weitzman CC, Baum RA, Fussell J, et al. Defining Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2022;149(4):e2021054771. doi:10.1542/peds.2021-054771

35. Center for the Study of Social Policy. Pediatrics Supporting Parents: Program and Site Selection Process and Results. Center for the Study of Social Policy; 2019. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://cssp.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/PEDIATRIACS-SUPPORTING-PARENTS-MEMO.pdf (PDF - 327 KB)

36. Doyle S, Chavez S, Cohen S, Morrison S. Fostering Social and Emotional Health through Pediatric Primary Care: Common Threads to Transform Everyday Practice and Systems—Executive Summary. Center for the Study of Social Policy; 2019. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://cssp.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Fostering-Social-Emotional-Health-Executive-Summary-1.pdf (PDF - 672 KB)

37. Doyle S, Chavez S, Cohen S, Morrison S. Fostering Social and Emotional Health through Pediatric Primary Care: Common Threads to Transform Practice and Systems. Center for the Study of Social Policy; 2019. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://cssp.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Fostering-Social-Emotional-Health-Full-Report.pdf (PDF - 1.4 MB)

38. Alderman EM, Breuner CC, COMMITTEE ON ADOLESCENCE, et al. Unique Needs of the Adolescent. Pediatrics. 2019;144(6):e20193150. doi:10.1542/peds.2019-3150

39. Confidentiality Protections for Adolescents and Young Adults in the Health Care Billing and Insurance Claims Process. Pediatrics. 2016;137(5):e20160593. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-0593

40. Sharko M, Jameson R, Ancker JS, Krams L, Webber EC, Rosenbloom ST. State-by-State Variability in Adolescent Privacy Laws. Pediatrics. 2022;149(6):e2021053458. doi:10.1542/peds.2021-053458

41. Kjolhede C, Lee AC, Duncan De Pinto C, et al. School-Based Health Centers and Pediatric Practice. Pediatrics. 2021;148(4):e2021053758. doi:10.1542/peds.2021-053758

42. DiGiovanni SS, Hoffmann Frances RJ, Brown RS, et al. Pediatric Trauma and Posttraumatic Symptom Screening at Well-child Visits. Pediatric Quality & Safety. 2023;8(3):e640. doi:10.1097/pq9.0000000000000640

43. Growing Resilience in Teens: A Year of Growth. Center for Injury Research and Prevention. April 1, 2025. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://injury.research.chop.edu/blog/posts/growing-resilience-teens-year-growth

44. Nordin JD, Solberg LI, Parker ED. Adolescent Primary Care Visit Patterns. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(6):511-516. doi:10.1370/afm.1188

45. Tsai Y, Zhou F, Wortley P, Shefer A, Stokley S. Trends and Characteristics of Preventive Care Visits among Commercially Insured Adolescents, 2003–2010. J Pediatr. 2014;164(3):625-630. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.10.042

46. Dempsey AF, Freed GL. Health care utilization by adolescents on medicaid: implications for delivering vaccines. Pediatrics. 2010;125(1):43-49. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-1044

47. Van Eck K, Thakkar M, Matson PA, Hao L, Marcell AV. Adolescents’ Patterns of Well-Care Use Over Time: Who Stays Connected. Am J Prev Med. 2021;60(5):e221-e229. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2020.12.008

48. Marcell AV, Matson P, Ellen JM, Ford CA. Annual physical examination reports vary by gender once teenagers become sexually active. J Adolesc Health. 2011;49(1):47-52. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.10.006

49. Garney W, Wilson K, Ajayi KV, et al. Social-Ecological Barriers to Access to Healthcare for Adolescents: A Scoping Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(8):4138. doi:10.3390/ijerph18084138

50. Garner A, Yogman M, COMMITTEE ON PSYCHOSOCIAL ASPECTS OF CHILD AND FAMILY HEALTH SODABP COUNCIL ON EARLY CHILDHOOD. Preventing Childhood Toxic Stress: Partnering With Families and Communities to Promote Relational Health. Pediatrics. 2021;148(2):e2021052582. doi:10.1542/peds.2021-052582

51. Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, THE COMMITTEE ON PSYCHOSOCIAL ASPECTS OF CHILD AND FAMILY HEALTH COEC ADOPTION, AND DEPENDENT CARE, AND SECTION ON DEVELOPMENTAL AND BEHAVIORAL PEDIATRICS, et al. The Lifelong Effects of Early Childhood Adversity and Toxic Stress. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e232-e246. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2663

52. Schofield TJ, Lee RD, Merrick MT. Safe, Stable, Nurturing Relationships as a Moderator of Intergenerational Continuity of Child Maltreatment: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;53(4):S32-S38. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.05.004

53. Huang CX, Halfon N, Sastry N, Chung PJ, Schickedanz A. Positive Childhood Experiences and Adult Health Outcomes. Pediatrics. 2023;152(1):e2022060951. doi:10.1542/peds.2022-060951

54. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Risk and Protective Factors. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). July 11, 2024. Accessed March 20, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/aces/risk-factors/index.html

55. Bethell C, Jones J, Gombojav N, Linkenbach J, Sege R. Positive Childhood Experiences and Adult Mental and Relational Health in a Statewide Sample: Associations Across Adverse Childhood Experiences Levels. JAMA Pediatrics. 2019;173(11):e193007. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.3007

56. Kosterman R, Mason WA, Haggerty KP, Hawkins JD, Spoth R, Redmond C. Positive Childhood Experiences and Positive Adult Functioning: Prosocial Continuity and the Role of Adolescent Substance Use. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;49(2):180-186. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.11.244

57. Mesman E, Vreeker A, Hillegers M. Resilience and mental health in children and adolescents: an update of the recent literature and future directions. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2021;34(6):586-592. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000741

58. Soleimanpour S, Cushing K, Christensen J, et al. Findings from the 2022 National Census of School-Based Health Centers. School-Based Health Alliance; 2023. https://sbh4all.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/FINDINGS-FROM-THE-2022-NATIONAL-CENSUS-OF-SCHOOL-BASED-HEALTH-CENTERS-09.20.23.pdf (PDF - 4.3 MB)

59. Panchal N, Cox C, Published RR. The Landscape of School-Based Mental Health Services. KFF. September 6, 2022. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://www.kff.org/mental-health/issue-brief/the-landscape-of-school-based-mental-health-services/

60. Yonek J, Lee CM, Harrison A, Mangurian C, Tolou-Shams M. Key Components of Effective Pediatric Integrated Mental Health Care Models: A Systematic Review. JAMA Pediatrics. 2020;174(5):487-498. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0023

61. Njoroge WFM, Hostutler CA, Schwartz BS, Mautone JA. Integrated Behavioral Health in Pediatric Primary Care. FOC. 2017;15(3):347-353. doi:10.1176/appi.focus.150302

62. Schlesinger A, Sengupta S, Marx L, et al. Clinical Update: Collaborative Mental Health Care for Children and Adolescents in Pediatric Primary Care. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2023;62(2):91-119. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2022.06.007

63. Smith JD, Cruden GH, Rojas LM, et al. Parenting Interventions in Pediatric Primary Care: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics. 2020;146(1):e20193548. doi:10.1542/peds.2019-3548

64. Assaf RR, Dolce M, Garg A. Sustainably Implementing Social Determinants of Health Interventions in the Pediatric Emergency Department. JAMA Pediatrics. 2024;178(1):9-10. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.4949

65. Steele DW, Becker SJ, Danko KJ, et al. Interventions for Substance Use Disorders in Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ); 2020. doi:10.23970/AHRQEPCCER225

66. Duong MT, Bruns EJ, Lee K, et al. Rates of Mental Health Service Utilization by Children and Adolescents in Schools and Other Common Service Settings: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2021;48(3):420-439. doi:10.1007/s10488-020-01080-9

67. Dray J, Bowman J, Campbell E, et al. Systematic Review of Universal Resilience-Focused Interventions Targeting Child and Adolescent Mental Health in the School Setting. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2017;56(10):813-824. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2017.07.780

68. Peters KM, Sadler G, Miller E, Radovic A. An Electronic Referral and Social Work Protocol to Improve Access to Mental Health Services. Pediatrics. 2018;142(5):e20172417. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-2417

69. Young ND, Mathews BL, Pan AY, Herndon JL, Bleck AA, Takala CR. Warm Handoff, or Cold Shoulder? An Analysis of Handoffs for Primary Care Behavioral Health Consultation on Patient Engagement and Systems Utilization. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology. 2020;8(3):241-246. doi:10.1037/cpp0000360

70. Hostutler C, Wolf N, Snider T, Butz C, Kemper AR, Butter E. Increasing Access to and Utilization of Behavioral Health Care Through Integrated Primary Care. Pediatrics. 2023;152(6):e2023062514. doi:10.1542/peds.2023-062514

71. Bright Futures. Promoting Healthy Mental Development: Developmental Screening in Adolescence. Accessed March 20, 2025. https://www.brightfutures.org/development/adolescence/overview_screening.html

72. Pratt LA, Brody DJ. Implications of two-stage depression screening for identifying persons with thoughts of self-harm. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2014;36(1):119-123. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.09.007

73. Anand P, Bhurji N, Williams N, Desai N. Comparison of PHQ-9 and PHQ-2 as Screening Tools for Depression and School Related Stress in Inner City Adolescents. J Prim Care Community Health. 2021;12:21501327211053750. doi:10.1177/21501327211053750

74. Richardson LP, Rockhill C, Russo JE, et al. Evaluation of the PHQ-2 as a Brief Screen for Detecting Major Depression Among Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010;125(5):e1097-e1103. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-2712

75. Allgaier AK, Pietsch K, Frühe B, Sigl-Glöckner J, Schulte-Körne G. Screening for Depression in Adolescents: Validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire in Pediatric Care. Depression and Anxiety. 2012;29(10):906-913. doi:10.1002/da.21971

76. Liu FF, Adrian MC. Is Treatment Working? Detecting Real Change in the Treatment of Child and Adolescent Depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2019;58(12):1157-1164. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2019.02.011

77. Llistosella M, Goni-Fuste B, Martín-Delgado L, et al. Effectiveness of resilience-based interventions in schools for adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2023;14. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1211113

78. Pinto TM, Laurence PG, Macedo CR, Macedo EC. Resilience Programs for Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Psychol. 2021;12. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.754115

79. Hodder RK, Freund M, Wolfenden L, et al. Systematic review of universal school-based ‘resilience’ interventions targeting adolescent tobacco, alcohol or illicit substance use: A meta-analysis. Preventive Medicine. 2017;100:248-268. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.04.003

80. Knopf JA, Finnie RKC, Peng Y, et al. School-Based Health Centers to Advance Health Equity: A Community Guide Systematic Review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2016;51(1):114-126. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2016.01.009