Purpose

Care of patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) is a natural fit for primary care and its fundamental strengths: respect for the patient, long-term clinical relationships, non-stigmatizing support, a degree of comfort with uncertainty, and a focus on whole-person care.1,2,3,4

All that is missing is a prescription for buprenorphine.

But we know things are not that simple. In 2017, fewer than 10 percent of primary care clinicians prescribed buprenorphine for OUD.5,6,7 Many studies have examined the barriers clinicians face in providing treatment for patients with OUD. Clinicians frequently cite logistical issues, including lack of time and support from staff, concerns about insurance reimbursement, need for prior authorizations, and regulatory factors, as common barriers to providing care for patients with OUD.8,9,10,11 One regulatory barrier, obtaining an X waiver to prescribe buprenorphine for patients with OUD, has been legally removed as of December 2022.12,13

Thousands of people are dying for lack of treatment and yet providers say there is no demand for treatment.14 People with OUD are harmed every day even as they desperately try to access prescribed buprenorphine.15 Adjusted estimates suggest past-year OUD affected over 7.5 million individuals in the U.S., but only 13% received FDA-approved medications.16 How can this circumstance be seen as “lack of patient demand” in primary care? When asked about the drivers of the OUD treatment gap, patients frequently cited stigma, prior negative experiences with OUD treatment, high out-of-pocket costs, and logistical issues, including difficulty finding a buprenorphine provider, provider waiting lists, and delays in buprenorphine initiation.17,18,19 Patients anticipate being rejected and do not trust healthcare to work for them.20,21

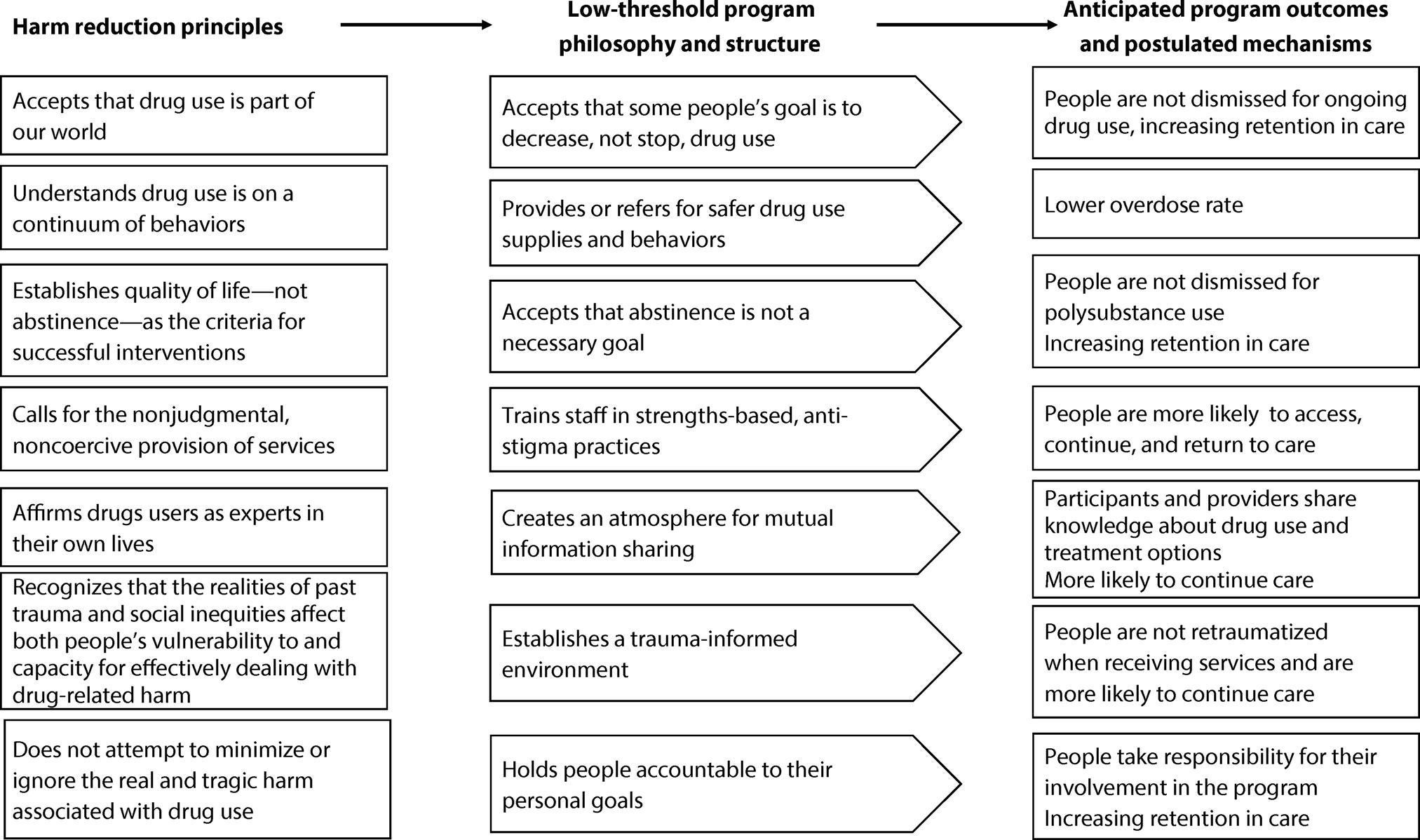

Low-threshold treatment addresses those deeper barriers that remain. By keeping its focus on patient health and safety, low-threshold treatment emphasizes medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) through the removal of barriers, which allows profound healing to happen in the primary care setting. To get started, we need patients who trust primary care to help, and clinicians who will do so.

This brief provides an overview of what constitutes low-threshold treatment for patients with OUD, the state of the evidence and patient perspectives on low-threshold OUD treatment, and key steps and strategies for providing low-threshold treatment for patients with OUD in primary care settings. Additionally, this brief outlines recommendations for how policymakers can improve and expand the provision of low-threshold treatment for patients with OUD in primary care settings.

Authors

- Monique Thornton, MPH - CEO, Let's Talk Public Health

- Stephen A. Martin, MD - Professor, UMass Chan Medical School

- Garrett E. Moran, PhD - Principal, Moran Consulting

- Noah Nesin, MD, FAAFP - Medical Director, Research & Innovation - Community Care Partnership of Maine

Other Contributors

- Danielle Durant, PhD, MS, MS, MBA - Principal Research Associate, Westat

- Rebecca Noftsinger, BA - Senior Study Director, Westat

- Joshua K. Noda, MPP - Principal Research Associate, Westat

Acknowledgements

We thank reviewers and other contributors from the Agency of Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ), National Integration Academy Council (NIAC), and Westat for sharing their time and expertise to develop, improve, and publish this work.

Suggested Citation

Thornton M, Martin SA, Moran GE, Nesin N. The Role of Low-Threshold Treatment for Patients with OUD in Primary Care. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; October 2023. https://integrationacademy.ahrq.gov/products/topic-briefs/oud-low-threshold-treatment.

[1] Hsu YJ, Marsteller JA, Kachur SG, Fingerhood MI. Integration of buprenorphine treatment with primary care: Comparative effectiveness on retention, utilization, and cost. Popul Health Manag. 2019 Aug;22(4):292-299. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2018.0163. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[2] Korthuis PT, McCarty D, Weimer M, Bougatsos C, Blazina I, Zakher B, Grusing S, Devine B, Chou R. Primary care-based models for the treatment of opioid use disorder: A scoping review. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Feb 21;166(4):268-278. https://doi.org/10.7326/m16-2149. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[3] Buresh M, Stern R, Rastegar D. Treatment of opioid use disorder in primary care. BMJ. 2021;373:n784. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n784. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[4] Incze MA, Chen D, Galyean P, Kimball ER, Stolebarger L, Zickmund S, Gordon AJ. Examining the primary care experience of patients with opioid use disorder: A qualitative study. J Addict Med. 2023 Jul-Aug 01;17(4):401-406. https://doi.org/10.1097/adm.0000000000001140. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[5] Abraham R, Wilkinson E, Jabbarpour Y, Bazemore A. Family physicians play key role in bridging the gap in access to opioid use disorder treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2020 Jul 1;102(1):10. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32603069/. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[6] McGinty EE, Stone EM, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Bachhuber MA, Barry CL. Medication for opioid use disorder: A national survey of primary care physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Jul 21;173(2):160-162. https://doi.org/10.7326%2FM19-3975. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[7] McBain RK, Dick A, Sorbero M, Stein BD. Growth and distribution of buprenorphine-waivered providers in the United States, 2007-2017. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Apr 7;172(7):504-506. https://doi.org/10.7326%2FM19-2403. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[8] Mackey K, Veazie S, Anderson J, Bourne D, Peterson K. Barriers and facilitators to the use of medications for opioid use disorder: A rapid review. J Gen Intern Med. 2020 Dec;35(Suppl 3):954-963. https://doi.org/10.1007%2Fs11606-020-06257-4. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[9] Austin EJ, Chen J, Briggs ES, et al. Integrating opioid use disorder treatment into primary care settings. AMA Netw Open. 2023 Aug 1;6(8):e2328627. https://doi.org/10.1001%2Fjamanetworkopen.2023.28627. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[10] Tofighi B, Williams AR, Chemi C, Suhail-Sindhu S, Dickson V, Lee JD. Patient barriers and facilitators to medications for opioid use disorder in primary care. Subst Use Misuse. 2019;54(14):2409-2419. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2019.1653324. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[11] Gordon AJ, Kenny M, Dungan M, Gustavson AM, Kelley AT, Jones AL, Hawkins E, Frank JW, Danner A, Liberto J, Hagedorn H. Are x-waiver trainings enough? Facilitators and barriers to buprenorphine prescribing after x-waiver trainings. Am J Addict. 2022 Mar;31(2):152-158. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajad.13260. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[12] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Waiver Elimination (MAT Act). https://www.samhsa.gov/medications-substance-use-disorders/waiver-elimination-mat-act. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[13] Gordon AJ, Kenny M, Dungan M, Gustavson AM, Kelley AT, Jones AL, Hawkins E, Frank JW, Danner A, Liberto J, Hagedorn H. Are x-waiver trainings enough? Facilitators and barriers to buprenorphine prescribing after x-waiver trainings. Am J Addict. 2022 Mar;31(2):152-158. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajad.13260. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[14] Jones CM, Olsen Y, Ali MM, Sherry TB, Mcaninch J, Creedon T, Juliana P, Jacobus-Kantor L, Baillieu R, Diallo MM, Thomas A, Gandotra N, Sokolowska M, Ling S, Compton W. Characteristics and prescribing patterns of clinicians waivered to prescribe buprenorphine for opioid use disorder before and after release of new practice guidelines. JAMA Health Forum. 2023 Jul 7;4(7):e231982. https://doi.org/10.1001%2Fjamahealthforum.2023.1982. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[15] Jones CM, Han B, Baldwin GT, Einstein EB, Compton WM. Use of medication for opioid use disorder among adults with past-year opioid use disorder in the US, 2021. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Aug 1;6(8):e2327488. https://doi.org/10.1001%2Fjamanetworkopen.2023.27488. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[16] Krawczyk N, Rivera BD, Jent V, Keyes KM, Jones CM, Cerdá M. Has the treatment gap for opioid use disorder narrowed in the U.S.?: A yearly assessment from 2010 to 2019. Int J Drug Policy. 2022 Dec;110:103786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103786. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[17] Mackey K, Veazie S, Anderson J, Bourne D, Peterson K. Barriers and facilitators to the use of medications for opioid use disorder: A rapid review. J Gen Intern Med. 2020 Dec;35(Suppl 3):954-963. https://doi.org/10.1007%2Fs11606-020-06257-4. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[18] Austin EJ, Chen J, Briggs ES, et al. Integrating opioid use disorder treatment into primary care settings. AMA Netw Open. 2023 Aug 1;6(8):e2328627. https://doi.org/10.1001%2Fjamanetworkopen.2023.28627. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[19] Tofighi B, Williams AR, Chemi C, Suhail-Sindhu S, Dickson V, Lee JD. Patient barriers and facilitators to medications for opioid use disorder in primary care. Subst Use Misuse. 2019;54(14):2409-2419. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2019.1653324. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[20] Carlberg-Racich S, Sherrod D, Swope K, Brown D, Afshar M, Salisbury-Afshar E. Perceptions and experiences with evidence-based treatments among people who use opioids. J Addict Med. 2023 Mar-Apr 01;17(2):169-173. https://doi.org/10.1097/adm.0000000000001064. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[21] Hooker SA, Sherman MD, Lonergan-Cullum M, Nissly T, Levy R. What is success in treatment for opioid use disorder? Perspectives of physicians and patients in primary care settings. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2022 Oct;141:108804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2022.108804. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[22] Missouri Opioid State Targeted Response. Medication First Model for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder. https://www.careinnovations.org/wp-content/uploads/MedicationFirstApproach_1pager-1-1.pdf (PDF - 189 KB). Accessed September 18, 2023.

[23] Jakubowski A, Fox A. Defining low-threshold buprenorphine treatment. J Addict Med. 2020 Mar/Apr;14(2):95-98. https://doi.org/10.1097%2FADM.0000000000000555. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[24] University of Pennsylvania Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics. Lowering the Barriers to Medication Treatment for People with Opioid Use Disorder. https://ldi.upenn.edu/our-work/research-updates/lowering-the-barriers-to-medication-treatment-for-people-with-opioid-use-disorder/. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[25] Martin SA, Chiodo LM, Bosse JD, Wilson A. The next stage of buprenorphine care for opioid use disorder. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Nov 6;169(9):628-635. https://doi.org/10.7326/m18-1652. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[26] Grande LA, Cundiff D, Greenwald MK, Murray M, Wright TE, Martin SA. Evidence on buprenorphine dose limits: A review. J Addict Med. 2023 Jun 16. https://doi.org/10.1097/adm.0000000000001189. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[27] Bhatraju EP, Grossman E, Tofighi B, McNeely J, DiRocco D, Flannery M, Garment A, Goldfeld K, Gourevitch MN, Lee JD. Public sector low threshold office-based buprenorphine treatment: Outcomes at year 7. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2017;12(1):7. https://doi.org/10.1186%2Fs13722-017-0072-2. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[28] Alford DP, LaBelle CT, Richardson JM, O'Connell JJ, Hohl CA, Cheng DM, Samet JH. Treating homeless opioid dependent patients with buprenorphine in an office-based setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(2):171-176. https://doi.org/10.1007%2Fs11606-006-0023-1. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[29] Lee CS, Rosales R, Stein MD, Nicholls M, O'Connor BM, Loukas Ryan V, Davis EA. Brief Report: Low-barrier buprenorphine initiation predicts treatment retention among Latinx and Non-Latinx primary care patients. Am J Addict. 2019 Sep;28(5):409-412. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajad.12925. Accessed September 28, 2023.

[30] Mutter R, Spencer D, McPheeters J. Outcomes associated with treatment with and without medications for opioid use disorder. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2023 Oct;50(4):524-539. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-023-09841-8. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[31] Krawczyk N, Buresh M, Gordon MS, Blue TR, Fingerhood MI, Agus D. Expanding low-threshold buprenorphine to justice-involved individuals through mobile treatment: Addressing a critical care gap. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019 Aug;103:1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2019.05.002. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[32] Jakubowski A, Lu T, DiRenno F, Jadow B, Giovanniello A, Nahvi S, Cunningham C, Fox A. Same-day vs. delayed buprenorphine prescribing and patient retention in an office-based buprenorphine treatment program. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020 Dec;119:108140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108140. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[33] Roy PJ, Price R, Choi S, Weinstein ZM, Bernstein E, Cunningham CO, Walley AY. Shorter outpatient wait-times for buprenorphine are associated with linkage to care post-hospital discharge. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021 Jul 1;224:108703. https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.drugalcdep.2021.108703. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[34] Simon CB, Tsui JI, Merrill JO, Adwell A, Tamru E, Klein JW. Linking patients with buprenorphine treatment in primary care: Predictors of engagement. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;181:58-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.09.017. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[35] Weinstein LC, Iqbal Q, Cunningham A, Debates R, Landistratis G, Doggett P, Silverio A. Retention of patients with multiple vulnerabilities in a federally qualified health center buprenorphine program: Pennsylvania, 2017-2018. Am J Public Health. 2020 Apr;110(4):580-586. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305525. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[36] Cunningham CO, Giovanniello A, Kunins HV, Roose RJ, Fox AD, Sohler NL. Buprenorphine treatment outcomes among opioid-dependent cocaine users and non-users. Am J Addict. 2013 Jul-Aug;22(4):352-7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.12032.x. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[37] Kapadia SN, Griffin JL, Waldman J, Ziebarth NR, Schackman BR, Behrends CN. A harm reduction approach to treating opioid use disorder in an independent primary care practice: A qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2021 Jul;36(7):1898-1905. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06409-6. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[38] Aronowitz SV, Engel-Rebitzer E, Lowenstein M, Meisel Z, Anderson E, South E. "We have to be uncomfortable and creative": Reflections on the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on overdose prevention, harm reduction & homelessness advocacy in Philadelphia. SSM Qual Res Health. 2021 Dec;1:100013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmqr.2021.100013. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[39] Wang L, Weiss J, Ryan EB, Waldman J, Rubin S, Griffin JL. Telemedicine increases access to buprenorphine initiation during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021 May;124:108272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108272. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[40] Harris R, Rosecrans A, Zoltick M, Willman C, Saxton R, Cotterell M, Bell J, Blackwell I, Page KR. Utilizing telemedicine during COVID-19 pandemic for a low-threshold, street-based buprenorphine program. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022 Jan 1;230:109187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109187. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[41] Nordeck CD, Buresh M, Krawczyk N, Fingerhood M, Agus D. Adapting a low-threshold buprenorphine program for vulnerable populations during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Addict Med. 2021 Sep-Oct 01;15(5):364-369. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000774. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[42] Weintraub E, Greenblatt AD, Chang J, Welsh CJ, Berthiaume AP, Goodwin SR, Arnold R, Himelhoch SS, Bennett ME, Belcher AM. Outcomes for patients receiving telemedicine-delivered medication-based treatment for Opioid Use Disorder: A retrospective chart review. Heroin Addict Relat Clin Probl. 2021;23(2):5-12. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7861202/. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[43] Bhatraju EP, Grossman E, Tofighi B, McNeely J, DiRocco D, Flannery M, Garment A, Goldfeld K, Gourevitch MN, Lee JD. Public sector low threshold office-based buprenorphine treatment: Outcomes at year 7. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2017 Feb 28;12(1):7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-017-0072-2. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[44] Carroll KM, Weiss RD. The role of behavioral interventions in buprenorphine maintenance treatment: A review. Am J Psychiatry. 2017 Aug 1;174(8):738-747. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16070792. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[45] Mutter R, Spencer D, McPheeters J. Outcomes associated with treatment with and without medications for opioid use disorder. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2023 Oct;50(4):524-539. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-023-09841-8. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[46] D'Onofrio G, O'Connor PG, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, Busch SH, Owens PH, Bernstein SL, Fiellin DA. Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015 Apr 28;313(16):1636-44. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.3474. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[47] Busch SH, Fiellin DA, Chawarski MC, Owens PH, Pantalon MV, Hawk K, Bernstein SL, O'Connor PG, D'Onofrio G. Cost-effectiveness of emergency department-initiated treatment for opioid dependence. Addiction. 2017 Nov;112(11):2002-2010. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13900. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[48] D'Onofrio G, Chawarski MC, O'Connor PG, Pantalon MV, Busch SH, Owens PH, Hawk K, Bernstein SL, Fiellin DA. Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine for opioid dependence with continuation in primary care: Outcomes during and after intervention. J Gen Intern Med. 2017 Jun;32(6):660-666. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-3993-2. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[49] Lowenstein M, Perrone J, Xiong RA, Snider CK, O'Donnell N, Hermann D, Rosin R, Dees J, McFadden R, Khatri U, Meisel ZF, Mitra N, Delgado MK. Sustained implementation of a multicomponent strategy to increase emergency department-initiated interventions for opioid use disorder. Ann Emerg Med. 2022 Mar;79(3):237-248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2021.10.012. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[50] Bachhuber MA, Thompson C, Prybylowski A, Benitez J MSW, Mazzella S MA, Barclay D. Description and outcomes of a buprenorphine maintenance treatment program integrated within Prevention Point Philadelphia, an urban syringe exchange program. Subst Abus. 2018;39(2):167-172. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2018.1443541. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[51] Hood JE, Banta-Green CJ, Duchin JS, Breuner J, Dell W, Finegood B, Glick SN, Hamblin M, Holcomb S, Mosse D, Oliphant-Wells T, Shim MM. Engaging an unstably housed population with low-barrier buprenorphine treatment at a syringe services program: Lessons learned from Seattle, Washington. Subst Abus. 2020;41(3):356-364. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2019.1635557. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[52] Weintraub E, Seneviratne C, Anane J, Coble K, Magidson J, Kattakuzhy S, Greenblatt A, Welsh C, Pappas A, Ross TL, Belcher AM. Mobile telemedicine for buprenorphine treatment in rural populations with opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Aug 2;4(8):e2118487. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.18487. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[53] Krawczyk N, Buresh M, Gordon MS, Blue TR, Fingerhood MI, Agus D. Expanding low-threshold buprenorphine to justice-involved individuals through mobile treatment: Addressing a critical care gap. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019 Aug;103:1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2019.05.002. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[54] Carter J, Zevin B, Lum PJ. Low barrier buprenorphine treatment for persons experiencing homelessness and injecting heroin in San Francisco. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2019 May 6;14(1):20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-019-0149-1. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[55] Pepin MD, Joseph JK, Chapman BP, McAuliffe C, O'Donnell LK, Marano RL, Carreiro SP, Garcia EJ, Silk H, Babu KM. A mobile addiction service for community-based overdose prevention. Front Public Health. 2023 Jul 19;11:1154813. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1154813. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[56] Jawa R, Tin Y, Nall S, Calcaterra SL, Savinkina A, Marks LR, Kimmel SD, Linas BP, Barocas JA. Estimated clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness associated with provision of addiction treatment in US primary care clinics. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Apr 3;6(4):e237888. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.7888. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[57] Simon C, Brothers S, Strichartz K, Coulter A, Voyles N, Herdlein A, Vincent L. We are the researched, the researchers, and the discounted: The experiences of drug user activists as researchers. Int J Drug Policy. 2021 Dec;98:103364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103364. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[58] Friedrichs A, Spies M, Härter M, Buchholz A. Patient preferences and shared decision making in the treatment of substance use disorders: A systematic review of the literature. PLoS One. 2016 Jan 5;11(1):e0145817. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0145817. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[59] Kelley AT, Incze MA, Baylis JD, Calder SG, Weiner SJ, Zickmund SL, Jones AL, Vanneman ME, Conroy MB, Gordon AJ, Bridges JFP. Patient-centered quality measurement for opioid use disorder: Development of a taxonomy to address gaps in research and practice. Subst Abus. 2022 Dec;43(1):1286-1299. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2022.2095082. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[60] Mackay L, Kerr T, Fairbairn N, Grant C, Milloy MJ, Hayashi K. The relationship between opioid agonist therapy satisfaction and fentanyl exposure in a Canadian setting. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2021;16(1):26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-021-00234-w. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[61] Lowenstein M, Abrams MP, Crowe M, Shimamoto K, Mazzella S, Botcheos D, Bertocchi J, Westfahl S, Chertok J, Garcia KP, Truchil R, Holliday-Davis M, Aronowitz S. "Come try it out. Get your foot in the door:" Exploring patient perspectives on low-barrier treatment for opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2023 Jul 1;248:109915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2023.109915. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[62] Shatterproof. Shatterproof National Principles of Care. https://www.shatterproof.org/shatterproof-national-principles-care. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[63] Sue KL, Cohen S, Tilley J, Yocheved A. A plea from people who use drugs to clinicians: New ways to initiate buprenorphine are urgently needed in the fentanyl era. J Addict Med. 2022 Jul-Aug 01;16(4):389-391. https://doi.org/10.1097/adm.0000000000000952. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[64] Saini J, Johnson B, Qato DM. Self-reported treatment need and barriers to care for adults with opioid use disorder: The US National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2015 to 2019. Am J Public Health. 2022 Feb;112(2):284-295. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2021.306577. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[65] Saini J, Johnson B, Qato DM. Self-reported treatment need and barriers to care for adults with opioid use disorder: The US National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2015 to 2019. Am J Public Health. 2022 Feb;112(2):284-295. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2021.306577. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[66] Carlberg-Racich S, Sherrod D, Swope K, Brown D, Afshar M, Salisbury-Afshar E. Perceptions and experiences with evidence-based treatments among people who use opioids. J Addict Med. 2023 Mar-Apr 01;17(2):169-173. https://doi.org/10.1097/adm.0000000000001064. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[67] Carlberg-Racich S, Sherrod D, Swope K, Brown D, Afshar M, Salisbury-Afshar E. Perceptions and experiences with evidence-based treatments among people who use opioids. J Addict Med. 2023 Mar-Apr 01;17(2):169-173. https://doi.org/10.1097/adm.0000000000001064. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[68] Marchand K, Foreman J, MacDonald S, Harrison S, Schechter MT, Oviedo-Joekes E. Building healthcare provider relationships for patient-centered care: A qualitative study of the experiences of people receiving injectable opioid agonist treatment. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2020;15(1):7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-020-0253-y. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[69] Chai D, Rosic T, Panesar B, Sanger N, van Reekum EA, Marsh DC, Worster A, Thabane L, Samaan Z. Patient-reported goals of youths in canada receiving medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Aug 2;4(8):e2119600. https://doi.org/10.1001%2Fjamanetworkopen.2021.19600. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[70] Holloway K, Murray S, Buhociu M, Arthur A, Molinaro R, Chicken S, Thomas E, Courtney S, Spencer A, Wood R, Rees R, Walder S, Stait J. Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic for substance misuse services: Findings from a peer-led study. Harm Reduct J. 2022 Dec 12;19(1):140. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-022-00713-6. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[71] Young GJ, Hasan MM, Young LD, Noor-E-Alam M. Treatment experiences for patients receiving buprenorphine/naloxone for opioid use disorder: A qualitative study of patients' perceptions and attitudes. Subst Use Misuse. 2023;58(4):512-519. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2023.2177111. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[72] Denhov A, Topor A. The components of helping relationships with professionals in psychiatry: Users' perspective. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2012;58(4):417-424. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764011406811. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[73] Snow RL, Simon RE, Jack HE, Oller D, Kehoe L, Wakeman SE. Patient experiences with a transitional, low-threshold clinic for the treatment of substance use disorder: A qualitative study of a bridge clinic. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019 Dec;107:1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2019.09.003. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[74] Krawczyk N, Mojtabai R, Stuart EA, Fingerhood M, Agus D, Lyons BC, Weiner JP, Saloner B. Opioid agonist treatment and fatal overdose risk in a state-wide US population receiving opioid use disorder services. Addiction. 2020 Sep;115(9):1683-1694. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14991. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[75] Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, Indave BI, Degenhardt L, Wiessing L, Ferri M, Pastor-Barriuso R. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: Systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017 Apr 26;357:j1550. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j1550. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[76] Larochelle MR, Bernson D, Land T, Stopka TJ, Wang N, Xuan Z, Bagley SM, Liebschutz JM, Walley AY. Medication for opioid use disorder after nonfatal opioid overdose and association with mortality: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Aug 7;169(3):137-145. https://doi.org/10.7326/m17-3107. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[77] Amato L, Minozzi S, Davoli M, Vecchi S. Psychosocial combined with agonist maintenance treatments versus agonist maintenance treatments alone for treatment of opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Oct 5;(10):CD004147. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd004147.pub4. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[78] Dugosh K, Abraham A, Seymour B, McLoyd K, Chalk M, Festinger D. A systematic review on the use of psychosocial interventions in conjunction with medications for the treatment of opioid addiction. J Addict Med. 2016 Mar-Apr;10(2):93-103. https://doi.org/10.1097%2FADM.0000000000000193. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[79] Wyse JJ, Morasco BJ, Dougherty J, Edwards B, Kansagara D, Gordon AJ, Korthuis PT, Tuepker A, Lindner S, Mackey K, Williams B, Herreid-O'Neill A, Paynter R, Lovejoy TI. Adjunct interventions to standard medical management of buprenorphine in outpatient settings: A systematic review of the evidence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021 Nov 1;228:108923. https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.drugalcdep.2021.108923. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[80] The Risk of Misuse and Diversion of Buprenorphine for Opioid Use Disorder Appears to Be Low in Medicare Part D. Data in Brief. OEI-02-22-00160. Washington, DC: Office of Inspector General; May 2023. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/OEI-02-22-00160.asp. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[81] Han B, Jones CM, Einstein EB, Compton WM. Trends in and characteristics of buprenorphine misuse among adults in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Oct 1;4(10):e2129409. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.29409. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[82] Tanz LJ, Jones CM, Davis NL, Compton WM, Baldwin GT, Han B, Volkow ND. Trends and characteristics of buprenorphine-involved overdose deaths prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Jan 3;6(1):e2251856. https://doi.org/10.1001%2Fjamanetworkopen.2022.51856. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[83] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Waiver Elimination (MAT Act). https://www.samhsa.gov/medications-substance-use-disorders/waiver-elimination-mat-act. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[84] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Waiver Elimination (MAT Act). https://www.samhsa.gov/medications-substance-use-disorders/waiver-elimination-mat-act. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[85] Chambers LC, Hallowell BD, Zullo AR, Paiva TJ, Berk J, Gaither R, Hampson AJ, Beaudoin FL, Wightman RS. Buprenorphine dose and time to discontinuation among patients with opioid use disorder in the era of fentanyl. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(9):e2334540. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.34540. Accessed September 19, 2023.

[86] Blazes CK, Morrow JD. Reconsidering the usefulness of adding naloxone to buprenorphine. Front Psychiatry. 2020 Sep 11;11:549272. https://doi.org/10.3389%2Ffpsyt.2020.549272. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[87] Gregg J, Hartley J, Lawrence D, Risser A, Blazes C. The naloxone component of buprenorphine/naloxone: Discouraging misuse, but at what cost? J Addict Med. 2023 Jan-Feb 01;17(1):7-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/adm.0000000000001030. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[88] Nguemeni Tiako MJ, Dolan A, Abrams M, Oyekanmi K, Meisel Z, Aronowitz SV. Thematic analysis of state medicaid buprenorphine prior authorization requirements. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Jun 1;6(6):e2318487. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.18487. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[89] Legal Action Center. Spotlight on Legislation Limiting the Use of Prior Authorization for Substance Use Disorder Services and Medications. https://www.lac.org/resource/spotlight-on-legislation-limiting-the-use-of-prior-authorization-for-substance-use-disorder-services-and-medications. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[90] Mariani JJ, Mahony AL, Podell SC, Brooks DJ, Brezing C, Luo SX, Naqvi NH, Levin FR. Open-label trial of a single-day induction onto buprenorphine extended-release injection for users of heroin and fentanyl. Am J Addict. 2021 Sep;30(5):470-476. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajad.13193. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[91] Hassman H, Strafford S, Shinde SN, Heath A, Boyett B, Dobbins RL. Open-label, rapid initiation pilot study for extended-release buprenorphine subcutaneous injection. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2023 Jan 2;49(1):43-52. https://doi.org/10.1080/00952990.2022.2106574. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[92] Klusaritz H, Bilger A, Paterson E, Summers C, Barg FK, Cronholm PF, Saine ME, Sochalski J, Doubeni CA. Impact of stigma on clinician training for opioid use disorder care: A qualitative study in a primary care learning collaborative. Ann Fam Med. 2023 Feb;21(Suppl 2):S31-S38. https://doi.org/10.1370%2Fafm.2920. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[93] Sue KL, Chawarski M, Curry L, McNeil R, Coupet E Jr, Schwartz RP, Wilder C, Tsui JI, Hawk KF, D'Onofrio G, O'Connor PG, Fiellin DA, Edelman EJ. Perspectives of clinicians and staff at community-based opioid use disorder treatment settings on linkages with emergency department-initiated buprenorphine programs. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 May 1;6(5):e2312718. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.12718. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[94] Andrilla CHA, Coulthard C, Larson EH. Barriers Rural Physicians Face Prescribing Buprenorphine for Opioid Use Disorder. Ann Fam Med. 2017 Jul;15(4):359-362. https://doi.org/10.1370%2Fafm.2099. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[95] Sue KL, Chawarski M, Curry L, McNeil R, Coupet E Jr, Schwartz RP, Wilder C, Tsui JI, Hawk KF, D'Onofrio G, O'Connor PG, Fiellin DA, Edelman EJ. Perspectives of clinicians and staff at community-based opioid use disorder treatment settings on linkages with emergency department-initiated buprenorphine programs. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 May 1;6(5):e2312718. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.12718. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[96] Stigma of Addiction Summit: Innovation Abstracts. Washington, DC: National Academy Medicine Report; January 2023. https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Innovation-Abstract-Packet_final.pdf (PDF - 1.3 MB). Accessed September 18, 2023.

[97] Jakubowski A, Lu T, DiRenno F, Jadow B, Giovanniello A, Nahvi S, Cunningham C, Fox A. Same-day vs. delayed buprenorphine prescribing and patient retention in an office-based buprenorphine treatment program. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020 Dec;119:108140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108140. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[98] Roy PJ, Price R, Choi S, Weinstein ZM, Bernstein E, Cunningham CO, Walley AY. Shorter outpatient wait-times for buprenorphine are associated with linkage to care post-hospital discharge. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021 Jul 1;224:108703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108703. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[99] Simon CB, Tsui JI, Merrill JO, Adwell A, Tamru E, Klein JW. Linking patients with buprenorphine treatment in primary care: Predictors of engagement. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017 Dec 1;181:58-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.09.017. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[100] National Institute on Drug Abuse. Drug Use and Viral Infections (HIV, Hepatitis) DrugFacts. https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugfacts/drug-use-viral-infections-hiv-hepatitis. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[101] Saldana CS, Vyas DA, Wurcel AG. Soft tissue, bone, and joint infections in people who inject drugs. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2020 Sep;34(3):495-509. https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.idc.2020.06.007. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[102] Rich KM, Solomon DA. Medical complications of injection drug use - Part I. NEJM Evidence. 2023;2(2):EVIDra2200292. https://doi.org/10.1056/EVIDra2200292. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[103] Rich KM, Solomon DA. Medical complications of injection drug use - Part II. NEJM Evidence. 2023;2(3):EVIDra2300019. https://doi.org/10.1056/EVIDra2300019. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[104] Jones CM, McCance-Katz EF. Co-occurring substance use and mental disorders among adults with opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019 Apr 1;197:78-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.12.030. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[105] Streck JM, Parker MA, Bearnot B, Kalagher K, Sigmon SC, Goodwin RD, Weinberger AH. National trends in suicide thoughts and behavior among US adults with opioid use disorder from 2015 to 2020. Subst Use Misuse. 2022;57(6):876-885. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2022.2046102. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[106] Santo T Jr, Campbell G, Gisev N, Martino-Burke D, Wilson J, Colledge-Frisby S, Clark B, Tran LT, Degenhardt L. Prevalence of mental disorders among people with opioid use disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022 Sep 1;238:109551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109551. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[107] Zhu Y, Mooney LJ, Yoo C, Evans EA, Kelleghan A, Saxon AJ, Curtis ME, Hser YI. Psychiatric comorbidity and treatment outcomes in patients with opioid use disorder: Results from a multisite trial of buprenorphine-naloxone and methadone. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021 Nov 1;228:108996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108996. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[108] Rohner H, Gaspar N, Rosen H, Ebert T, Kilarski LL, Schrader F, Al Istwani M, Lenz AJ, Dilg C, Welskop A, Goldmann T, Schmidt U, Philipsen A. ADHD Prevalence among outpatients with severe opioid use disorder on daily intravenous diamorphine and/or oral opioid maintenance treatment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Jan 31;20(3):2534. https://doi.org/10.3390%2Fijerph20032534. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[109] Levin FR, Evans SM, Vosburg SK, Horton T, Brooks D, Ng J. Impact of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and other psychopathology on treatment retention among cocaine abusers in a therapeutic community. Addict Behav. 2004 Dec;29(9):1875-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.03.041. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[110] Kast KA, Rao V, Wilens TE. Pharmacotherapy for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and retention in outpatient substance use disorder treatment: A retrospective cohort study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021 Feb 23;82(2):20m13598. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.20m13598. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[111] National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About Chronic Diseases. https://www.cdc.gov/chronic-disease/about/index.html. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[112] Pan Y, Xu R. Mining comorbidities of opioid use disorder from FDA adverse event reporting system and patient electronic health records. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2022 Jun 16;22(Suppl 2):155. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-022-01869-8. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[113] Slawek DE, Lu TY, Hayes B, Fox AD. Caring for patients with opioid use disorder: What clinicians should know about comorbid medical conditions. Psychiatr Res Clin Pract. 2019 Apr 1;1(1):16-26. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.prcp.20180005. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[114] Anderson KE, Alexander GC, Niles L, Scholle SH, Saloner B, Dy SM. Quality of preventive and chronic illness care for insured adults with opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Apr 1;4(4):e214925. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.4925. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[115] Heil SH, Melbostad HS, Matusiewicz AK, Rey CN, Badger GJ, Shepard DS, Sigmon SC, MacAfee LK, Higgins ST. Efficacy and cost-benefit of onsite contraceptive services with and without incentives among women with opioid use disorder at high risk for unintended pregnancy: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021 Oct 1;78(10):1071-1078. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1715. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[116] Charron E, Kent-Marvick J, Gibson T, Taylor E, Bouwman K, Sani GM, Simonsen SE, Stone RH, Kaiser JE, McFarland MM. Barriers to and facilitators of hormonal and long-acting reversible contraception access and use in the US among reproductive-aged women who use opioids: A scoping review. Prev Med Rep. 2023 Jan 18;32:102111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2023.102111. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[117] Hurley EA, Goggin K, Piña-Brugman K, Noel-MacDonnell JR, Allen A, Finocchario-Kessler S, Miller MK. Contraception use among individuals with substance use disorder increases tenfold with patient-centered, mobile services: a quasi-experimental study. Harm Reduct J. 2023 Mar 6;20(1):28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-023-00760-7. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[118] Saini J, Johnson B, Qato DM. Self-reported treatment need and barriers to care for adults with opioid use disorder: The US National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2015 to 2019. Am J Public Health. 2022 Feb;112(2):284-295. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2021.306577. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[119] Jones CM, Han B, Baldwin GT, Einstein EB, Compton WM. Use of medication for opioid use disorder among adults with past-year opioid use disorder in the US, 2021. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Aug 1;6(8):e2327488. https://doi.org/10.1001%2Fjamanetworkopen.2023.27488. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[120] Jones CM, Shoff C, Hodges K, Blanco C, Losby JL, Ling SM, Compton WM. Receipt of telehealth services, receipt and retention of medications for opioid use disorder, and medically treated overdose among Medicare beneficiaries before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022 Oct 1;79(10):981-992. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.2284. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[121] Rand Corporation. The Solution to Telemedicine Prescribing of Buprenorphine Seems Clear to Everyone but DEA. https://www.rand.org/blog/2023/09/the-solution-to-telemedicine-prescribing-of-buprenorphine.html. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[122] Andraka-Christou B, Golan O, Totaram R, Ohama M, Saloner B, Gordon AJ, Stein BD. Prior authorization restrictions on medications for opioid use disorder: Trends in state laws from 2005 to 2019. Ann Med. 2023 Dec;55(1):514-520. https://doi.org/10.1080%2F07853890.2023.2171107. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[123] The Pew Charitable Trusts. Policies Should Promote Access to Buprenorphine for Opioid Use Disorder: State and federal leaders can eliminate barriers, boost treatment. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2021/05/policies-should-promote-access-to-buprenorphine-for-opioid-use-disorder. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[124] The Pew Charitable Trusts. Overview of Opioid Treatment Program Regulations by State. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2022/09/overview-of-opioid-treatment-program-regulations-by-state. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[125] Orgera K, Tolbert J. The Opioid Epidemic and Medicaid's Role in Facilitating Access to Treatment. San Francisco, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; May 2019. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-opioid-epidemic-and-medicaids-role-in-facilitating-access-to-treatment/. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[126] Clemans-Cope L, Lynch V, Payton M, Aarons J. Medicaid professional fees for treatment of opioid use disorder varied widely across states and were substantially below fees paid by Medicare in 2021. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2022 Jul 6;17(1):49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-022-00478-y. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[127] The Pew Charitable Trusts. Overview of Opioid Treatment Program Regulations by State. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2022/09/overview-of-opioid-treatment-program-regulations-by-state. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[128] Rand Corporation. The Solution to Telemedicine Prescribing of Buprenorphine Seems Clear to Everyone but DEA. https://www.rand.org/blog/2023/09/the-solution-to-telemedicine-prescribing-of-buprenorphine.html. Accessed September 18, 2023.

[129] The Pew Charitable Trusts. Policies Should Promote Access to Buprenorphine for Opioid Use Disorder: State and federal leaders can eliminate barriers, boost treatment. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2021/05/policies-should-promote-access-to-buprenorphine-for-opioid-use-disorder. Accessed September 18, 2023.